|

“The plain record shows that the trial judge denied a pro se litigant the most basic due process right of all: the opportunity to present evidence in support of his claim.”

-- Norman A. Olch

Chairman, Appellate Committee New York Bar Association |

The Marriage Lasted 10 Years.

The Lawsuits? 13 Years, and Counting.

It's a drizzly afternoon and the brightly lighted records room at the federal courthouse in Lower Manhattan is mostly empty save for a disheveled older man in sweat pants and a raincoat poring over documents.

The man, Michael Melnitzky, 69, has become something of a fixture here, as he has in courthouses across the city, busily preparing his next case.

Balding, with just a fringe of unwieldy gray hair, Mr. Melnitzky was once a recognized art expert. He was the principal art conservator at Sotheby's for nearly 30 years and had a client list that included Hollywood celebrities and denizens from high society. When Greta Garbo died, he was called on to examine her art collection.

But when his wife filed for divorce in 1994, Mr. Melnitzky became something else: a litigator. A prolific one. And although he has no law degree and only himself as a client, he has never been busier.

|

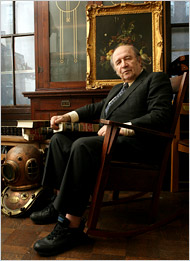

Michael Milnitzky has represented himself in an array of court cases, most related to a collection of watches worth a half-million dollars that he sought to keep after the divorce.

Photo courtesy of Fred R. Conrad/The New York Times |

Through a series of self-fashioned lawsuits and appeals, issues that might have been settled with his divorce have gone on for 13 years, 3 years longer than his marriage.

He has sued virtually everyone involved: one of his former lawyers, his wife's lawyer, three banks, five judges and a psychiatrist appointed by the court to evaluate his mental health. In unrelated cases, he has sued a neighbor, a thrift shop, the city and his former employer. And he has almost always lost.

Legal experts say Mr. Melnitzky is hardly alone among people who become fixated with the legal system, filing lawsuits again and again without the aid of a lawyer to try to reverse an earlier loss.

But Mr. Melnitzky is unusual because of the volume and complexity of his litigation, and because he arguably could afford a lawyer but has seldom chosen to use one, even in the face of repeated failure.

Mr. Melnitzky says he is just trying to right the wrongs done to him and, in the process, expose a civil court system he believes is intolerant of pro se litigants. The courts have struggled for years with how to handle litigants who represent themselves ("pro se" means "for oneself" in Latin).

The question is: Is Mr. Melnitzky's record of litigation a test of a flawed system, or an obsessive abuse of the courts? "I used to be an art restorer," he says. "Now I'm a litigator. If you're going to attack me or assault me on a legal front, and I don't hit back, I would feel dishonorable with myself."

Most of the litigation revolves around a collection of 750 watches, with an estimated value of a half-million dollars, that he says is a link to his family's survival in World War II Poland. While other members of Mr. Melnitzky's extended family died in the Holocaust, his father used watches, precious jewelry and other small valuables to pay off officials and to help trusted gentile friends who hid him.

After the war, the family came to the United States; Mr. Melnitzky and his father, who died in 1988, began slowly rebuilding the collection. Their treasures included timepieces by Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin and turn-of-the-century American watchmakers.

Mr. Melnitzky says all of the watches were purchased or inherited before he was married and so by New York law should not have been part of the marital estate. A judge disagreed. In a 1998 decision, Justice Walter B. Tolub of Manhattan Supreme Court ordered that about a quarter of the watches tagged with purchase dates before 1984 be returned to Mr. Melnitzky. The rest he ordered to be sold and the proceeds split with Mr. Melnitzky's ex-wife.

Mr. Melnitzky has spent nearly the last nine years trying to stop the sale. When not in court, he applies the same meticulous attention that he once put into restoring great Impressionist works to researching the law. Legal texts fill his cluttered brownstone on the Upper East Side, whose top floors he rents out.

Loquacious, with a wry humor, Mr. Melnitzky can be both engaging and abrasive. He ponders whether his need to keep fighting the courts stems from having escaped the Holocaust as a child, a survivor's guilt that drives him to test himself against what he sees as an unjust system.

In the last 10 years, he has lost 17 of 18 lawsuits — the remaining one is still active — and 30 of 32 appeals. The two appellate victories ultimately ended in defeats after the cases were returned to lower courts.

He has tested the patience of state judges at every level, been penalized by some and was once found in contempt. Some, like Justice Tolub, urged him to hire a lawyer. He refused.

Justice Tolub wrote in the 1998 ruling that the advantages of Mr. Melnitzky's decision to represent himself "soon became clear."

"Mr. Melnitzky was free to plead ignorance of the law when it suited him, at the same time picking and choosing those points of law which he 'discovered' were in his favor," the judge wrote.

As the number of pro se litigants has grown in recent years, judges across the country have struggled with the question of how far to ease the rules to help the self-represented while remaining fair to the party with counsel. A look at the records from Mr. Melnitzky's 1998 trial illustrates this struggle. But the documents also raise questions about his treatment.

In his 13-page ruling, Justice Tolub charged that Mr. Melnitzky had stonewalled the court to shield his assets, then "spent five-six days on witnesses to prove he was a Holocaust survivor" and other matters that had already been conceded.

On the last day of the trial, Mr. Melnitzky finally got around to his argument that the watches were not marital property, Justice Tolub wrote. When Mr. Melnitzky tried to present the invoices, however, the judge balked and ordered him to submit them in a post-trial motion.

"Will it be lawful?" Mr. Melnitzky asked.

"I worry about lawful," the judge said.

Five weeks later, when the judge returned from vacation, he found three volumes of documents from Mr. Melnitzky awaiting him. But despite Mr. Melnitzky's having followed his instructions, the judge ruled that considering his documents at that point would have been costly and highly prejudicial and would have unnecessarily prolonged the case.

Multiple appeals were unsuccessful, and no judge since has looked at the invoices, repeatedly ruling that the matter was already decided.

Mr. Melnitzky wasn't finished. A few years ago, he attended a legal training seminar for lawyers given by Norman A. Olch, then chairman of the New York Bar Association's appellate committee.

Afterward, Mr. Melnitzky called Mr. Olch and, as he had done with dozens of lawyers and clerks and judges before, he laid out the tangled details of his case. After reading the 1998 trial transcript and the subsequent appellate rulings, Mr. Olch became intrigued.

"It seemed to me he had basically followed the trial judge's directions in submitting the evidence," Mr. Olch said. "My sense was that his pro se motion had failed to crystallize that point."

In a 2005 brief to the New York Court of Appeals, the state's highest court, Mr. Olch wrote that while criminal courts had long recognized the need to give pro se defendants more latitude in pleading their arguments, Mr. Melnitzky's case illustrated a troubling gap in the civil courts' understanding of how to deal with pro se litigants. Common law does suggest that judges should give such litigants in civil cases some latitude, but it also requires that they be held to the same standards as those with lawyers.

"The plain record shows that the trial judge denied a pro se litigant the most basic due process right of all: the opportunity to present evidence in support of his claim," Mr. Olch wrote.

The Court of Appeals, which accepts only about 7 percent of the 1,000 applications for civil appeals it receives each year, declined to hear the case.

"I think the problem was that he came to me after he'd already gone through the first appeal," Mr. Olch said.

Mr. Melnitzky has since turned to the federal courts, again without a lawyer, and so far with the same lack of success. At a recent hearing, an opposing lawyer called him a "serial litigator" who was turning the legal system into a "hobby" at the expense of the people he sued.

Mr. Melnitzky takes exception to such characterizations, as he does to the mention of obsession.

"It's not an obsession; it's a cause," he said. "Would you call the fight against Nazis an obsession?"

The watches, meanwhile, have since begun to be sold. The auctions have been conducted in secret because, according to court records, officials of at least one prominent auction house worried that Mr. Melnitzky might sue them.

From: The New York Times, February 19, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/19/nyregion/..., accessed February 20, 2007. Reprinted in accordance with the "fair use" provision of Title 17 U.S.C.

Note: In 2019, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida prepared a guide for pro se filers that contains useful information generally applicable to other district courts.

|

THE ANTI-PRO-SE JUDICIARY

|

MISTREATMENT OF PRO SE'S

|