| Every day, through those menacing, threatening, screaming crowds, she entered the school. There, a white teacher, Miss Henry, met her, led her to an empty classroom, and her lessons began. |

Ruby Bridges' Long Walk

To heal. To minister. To inspire. To teach. To walk the walk. Ruby Bridges calls it "stepping out."

She was six the first time she did it. She was the first black child to walk into an

It was an era of American flash points. Ruby was in the cross hairs. She was a test case. She was on television. She walked up the front steps of William Frantz Elementary on North Galvez Street. Over the next few hours, a few hundred white kids walked out of the school and down those steps, many never to return.

In this simple, unwitting act — Ruby thought it was Mardi Gras: the barricades, all those policemen, the screaming people with their arms waving around — she became, literally, America's poster child for

For integration. Racism. Hatred. Innocence. Troubled times. They had come. To your hometown.

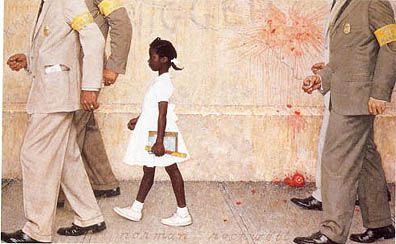

Norman Rockwell painted the poster: Ruby with four federal marshals towering above her. He called it "The Problem We All Live With." It became even more famous than her. Nobody knew what to make of it. What, folks wondered, is the problem?

Everyone had different ideas about that. This much we know: Ruby wasn't the problem. There, in the middle of the nation's simmering race war, the lines in the sand were drawn by adults. Often, their children became the foot soldiers. And Ruby walked alone. With four armed

Barack Hussein Obama. So young. So improbable. So polysyllabic. A rock star. A vessel.

"This is his time," Bridges said. "When he came out and gave his acceptance speech, it hit me; I could see in his demeanor and on his face that he had accepted what his purpose was. He seemed so humbled and so at peace. And I understand that look. And I know what that feeling is like. And you just step out and you go for it.

"You don't know if you have a day or a year; you just know you have to do it. I used to think about that a lot with Dr. King. That he had to know that he probably wasn't going to see the fruits of his labor. But he accepted it and he stepped out, every day, knowing that one day was going to be the day.

"And for me, that's kind of what I've done and what I do. I'm not really embraced like I think I should be. I don't think that I've taken my rightful place in history yet. But I step out every day, because I also believe in what I'm doing."

by Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

What Ruby Bridges does is talk to children. She can relate to them. She can walk their walk. After all, she transfixed and transformed a nation when she was one of them.

Every day, through those menacing, threatening, screaming crowds, she entered the school. There, a white teacher, Miss Henry, met her, led her to an empty classroom, and her lessons began.

For the entire school year, she sat amid a sea of empty desks, each one a symbol of hate, fear or ignorance. Or all three. Funny, though: She loved it. School, that is. Imagine, just you and your very best favorite teacher ever, alone together, all day, every day.

God bless Miss Henry. She was a rock of salvation. Long before most folks knew how to deal, she knew. She was from Boston. Maybe that made a difference, maybe it didn't. Her job was to teach. So she taught. No child left behind, indeed.

Ruby never cried in front of the crowd outside, though sometimes she stopped and prayed in their direction. The enormity of it all didn't really settle in for some time, for many years in fact. Because, by the fall of 1961 — a new school year — the crowds had dispersed, a mix of black and white kids enrolled at William Frantz and Ruby Bridges was just another student in another desk. Life went on. Eerily so, in fact.

"After that year, it was over," she said. "It had happened, but no one ever talked about it. It was as if it had been swept under the rug."

So she grew up. Graduated from Nicholls High, where no one knew her story. She went to business school in Kansas City. Became a travel agent for American Express. Traveled the world. Met a man. Became Mrs. Ruby Bridges Hall. Settled in eastern New Orleans. Had four sons. A normal life. Sort of. And then

And then her brother was shot and killed on the streets of New Orleans in 1993. His children were at William Frantz. So Ruby Bridges Hall walked back up those stairs and back into that school again. To help them. To help others. She volunteered as a mentor and parent liaison. And things started to happen.

In 1995, Robert Coles, Bridges' child psychiatrist, published a school textbook called "The Story of Ruby Bridges." In 1998, her story became a

She got used to the spotlight again, after all those decades out of it. And she embraced it. She decided it was her time to step out again.

Sitting on the front steps of William Frantz Elementary last week, she recounted it all, the reason she stepped out of anonymity and back into the battle.

The school has been boarded and derelict since the storm. She wants to get it fixed, get it chartered and open a school with a curriculum focusing on social justice. She'd like it to bear her name. She earned it on these mean streets.

"The whole experience was kind of haunting me," she said. "At some point, I needed to deal with it. It was important and I needed to do something about it. I realized that if I wanted to create a legacy, I was going to have to carry the torch myself."

In 1999, she formed the Ruby Bridges Foundation and began a career as a motivational speaker in schools. She travels around the country talking almost exclusively to children. She sees the world through a different prism than most. It gives her a fresh look at almost everything, and that would include Obama's election.

"I was speaking to someone the other day who said to me: 'Did you ever think this day would happen?' " she said. "And I said, 'Yes.' I've always felt like it would. I have an opportunity to see hope that a lot of people don't get a chance to see, simply because I spend my days in schools all across the country, sharing my story and talking about the lessons that I learned sitting in that empty classroom for a year.

"For me, it was the same lesson that King tried to pass on to all of us. Even though there was that mob of people outside that I would have to pass to get into my class, the minute I walked through those doors, there was a white woman there to greet me and she absolutely made school fun.

"She looked exactly like everybody else outside, but she showed me her heart and there was absolutely no way I could think she was the same as them. So the lesson I learned was that you can't look at a person and judge them — and I think that shaped me into who I am.

"So, for me, it's important to try to explain that to kids, the way I learned it. It's amazing how drawn to my story they are. And I think that's because they put themselves in the shoes of that little

Two of Bridges' sons are grown now and live in New Orleans. One was murdered on the streets of the city in 2005, following his uncle's fate, a few months before the storm. Her youngest son is still in high school and it is with him and her husband of more than 30 years that she has gone to Washington, D.C., to witness history: her history, our history.

She has put the word out that she'd like an audience with President Barack Obama. She has a signed copy of the Rockwell print as a gift for him.

"Let's face it: For a very long time, people knew that Rockwell painting, but they didn't know who that person was, or the real story behind it," she said. "Up until the books came out, nobody knew me or what I was doing. Rosa Parks, Dr. King, a couple other people — you've always heard about them. But you don't ever see me there with them. Maybe it's going to take a little more work.

"I think I have a positive message. I think mine is the one that's been in line with Obama's message: inclusion. That it's going to take all of us. That we're going too have to set our differences aside. That's the message that I've been delivering to our children for over 15 years. That has been my work, my faith. I believe my maker can use anybody to do his work. All of us. If we're open and allow ourselves to be used for good."

After the inauguration, Ruby Bridges' husband and son will fly home to New Orleans. She will continue on to Boston. She will spend a night at the home of Barbara Henry — yes, Miss Henry — who moved back there immediately after her school year with Ruby. They were reunited 40 years later.

They are friends now. They will do some school appearances together this week, this big, big week of remembrance, history and nostalgia.

Last week, several newspapers and Web sites ran simultaneous pictures of Sasha Obama's first day of school in Washington and of Ruby Bridges' first day at William Frantz. The connection — so long, tortured, serpentine, bloody, strained and, maybe, reconciled — needs so little explanation.

A woman who saw the pictures

But weep no more for Ruby Bridges. It is her time. She is stepping out again. One small step for a little girl so long ago and far away. One giant leap for America.

In Ruby's shoes.

Publishing Corporation

Additional Reading

- Leona Tate, "Gliding past mobs, toward an education," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, May 20, 2004,

Metro, p. 7 . - The McDonogh Three; In 1960, three first-grade girls integrated McDonogh No. 19. After years of trying to forget the storm that swirled around them, today they are proud of their roles," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, May 16, 2004,

National, p. 19 .

From: Chris Rose, "Ruby Bridges' long walk; An icon of New Orleans integration will witness another milestone 50 years later," The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, January 19, 2009, National,

|

|

|