|

Critiques of the Judiciary

|

|

|

Critiques of the Judiciary

|

|

Deceptive Prosecutors Ruled Immune from Accountability

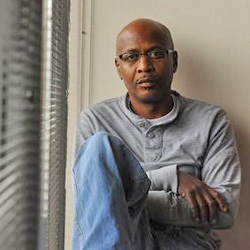

(Part 2)John Thompson reflects on his 18 years in prison for a murder he didn't commit.

Pace University law professor

NEW ORLEANS — I SPENT 18 years in prison for robbery and murder, 14 of them on death row. I've been free since 2003, exonerated after evidence covered up by prosecutors surfaced just weeks before my execution date. Those prosecutors were never punished. Last month, the Supreme Court1 decided 5-4 to overturn a case I'd won against them and the district attorney who oversaw my case, ruling that they were not liable for the failure to turn over that evidence — which included proof that blood at the robbery scene wasn't mine.

Because of that, prosecutors are free to do the same thing to someone else today.

I was arrested in January 1985 in New Orleans. I remember the police coming to my grandmother's house — we all knew it was the cops because of how hard they banged on the door before kicking it in. My grandmother and my mom were there, along with my little brother and sister, my two sons — John Jr., 4, and Dedric, 6 — my girlfriend and me. The officers had guns drawn and were yelling. I guess they thought they were coming for a murderer. All the children were scared and crying. I was 22.

John Thompson

John Thompson

Photo by Paddy MolloyThey took me to the homicide division, and played a cassette tape on which a man I knew named Kevin Freeman accused me of shooting a man. He had also been arrested as a suspect in the murder. A few weeks earlier he had sold me a ring and a gun; it turned out that the ring belonged to the victim and the gun was the murder weapon.

My picture was on the news, and a man called in to report that I looked like someone who had recently tried to rob his children. Suddenly I was accused of that crime, too. I was tried for the robbery first. My lawyers never knew there was blood evidence at the scene, and I was convicted based on the victims' identification.

After that, my lawyers thought it was best if I didn't testify at the murder trial. So I never defended myself, or got to explain that I got the ring and the gun from Kevin Freeman. And now that I officially had a history of violent crime because of the robbery conviction, the prosecutors used it to get the death penalty.

I remember the judge telling the courtroom the number of volts of electricity they would put into my body. If the first attempt didn't kill me, he said, they'd put more volts in.

On Sept. 1, 1987, I arrived on death row in the Louisiana State Penitentiary — the infamous Angola prison. I was put in a dead man's cell. His things were still there; he had been executed only a few days before. That past summer they had executed eight men at Angola. I received my first execution date right before I arrived. I would end up knowing 12 men who were executed there.

Over the years, I was given six execution dates, but all of them were delayed until finally my appeals were exhausted. The seventh — and last — date was set for May 20, 1999. My lawyers had been with me for 11 years by then; they flew in from Philadelphia to give me the news. They didn't want me to hear it from the prison officials. They said it would take a miracle to avoid this execution. I told them it was fine — I was innocent, but it was time to give up.

But then I remembered something about May 20. I had just finished reading a letter from my younger son about how he wanted to go on his senior class trip. I'd been thinking about how I could find a way to pay for it by selling my typewriter and radio. "Oh, no, hold on," I said, "that's the day before John Jr. is graduating from high school." I begged them to get it delayed; I knew it would hurt him.

To make things worse, the next day, when John Jr. was at school, his teacher read the whole class an article from the newspaper about my execution. She didn't know I was John Jr.'s dad; she was just trying to teach them a lesson about making bad choices. So he learned that his father was going to be killed from his teacher, reading the newspaper aloud. I panicked. I needed to talk to him, reassure him.

Amazingly, I got a miracle. The same day that my lawyers visited, an investigator they had hired to look through the evidence one last time found, on some forgotten microfiche, a report sent to the prosecutors on the blood type of the perpetrator of the armed robbery. It didn't match mine; the report, hidden for 15 years, had never been turned over to my lawyers. The investigator later found the names of witnesses and police reports from the murder case that hadn't been turned over either.

As a result, the armed robbery conviction was thrown out in 1999, and I was taken off death row. Then, in 2002, my murder conviction was thrown out. At a retrial the following year, the jury took only 35 minutes to acquit me.

The prosecutors involved in my two cases, from the office of the Orleans Parish district attorney, Harry Connick Sr., helped to cover up 10 separate pieces of evidence. And most of them are still able to practice law today.

Why weren't they punished for what they did? When the hidden evidence first surfaced, Mr. Connick announced that his office would hold a grand jury investigation. But once it became clear how many people had been involved, he called it off.

In 2005, I sued the prosecutors and the district attorney's office for what they did to me. The jurors heard testimony from the special prosecutor who had been assigned by Mr. Connick's office to the canceled investigation, who told them, "We should have indicted these guys, but they didn't and it was wrong." The jury awarded me $14 million in damages — $1 million for every year on death row — which would have been paid by the district attorney's office. That jury verdict is what the Supreme Court1 has just overturned.

I don't care about the money. I just want to know why the prosecutors who hid evidence, sent me to prison for something I didn't do and nearly had me killed are not in jail themselves. There were no ethics charges against them, no criminal charges, no one was fired and now, according to the Supreme Court,1 no one can be sued.

Worst of all, I wasn't the only person they played dirty with. Of the six men one of my prosecutors got sentenced to death, five eventually had their convictions reversed because of prosecutorial misconduct. Because we were sentenced to death, the courts had to appoint us lawyers to fight our appeals. I was lucky, and got lawyers who went to extraordinary lengths. But there are more than 4,000 people serving life without parole in Louisiana, almost none of whom have lawyers after their convictions are final. Someone needs to look at those cases to see how many others might be innocent.

If a private investigator hired by a generous law firm hadn't found the blood evidence, I'd be dead today. No doubt about it.

A crime was definitely committed in this case, but not by me.

Copyright 2015, The New York Times Company

From: John Thompson, "The Prosecution Rests, but I Can't," The New York Times, Op-Ed Contributor, April 9, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/10/opinion/10thompson.html, accessed 07/11/2015. John Thompson is the director of Resurrection After Exoneration, a support group for exonerated inmates. Reprinted in accordance with the "fair use" provision of Title 17 U.S.C.§ 107 for a non-profit educational purpose.

Holding Prosecutors AccountableINNOCENCE PROJECTAugust 31, 2011A recent Supreme Court decision begs the question of what, if anything, prosecutors can be held accountable for.

In 1985, John Thompson, a 22-year-old father of two, was wrongfully convicted of murder and sent to death row at Angola State Penitentiary in Louisiana. While facing his seventh execution date, a private investigator hired by his appellate attorneys discovered scientific evidence of Thompson's innocence that had been concealed for 15 years by the New Orleans Parish District Attorney's Office.

Thompson was released and exonerated in 2003 after 18 years in prison, 14 of them isolated on death row. The state of Louisiana gave him $10 and a bus ticket upon his release. He sued the District Attorney's Office. A jury awarded him $14 million, one for each year on death row. When Louisiana appealed, the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. This spring, Justice Clarence Thomas issued the majority 5-4 decision in Connick v. Thompson1 that the prosecutor's office could not be held liable.

The controversial and divided decision leaves Thompson with no choice but to get on with his life, which, incredibly, he already has. He is the founder and director of Resurrection after Exoneration, an organization that provides transitional housing to exonerees in the New Orleans area. Thompson's fortitude notwithstanding, his story has become a kind of cautionary tale of unchecked prosecutorial power. If prosecutors cannot be held accountable in this case, when can they be held accountable?

In an op-ed for The New York Times, Thompson writes, "I don't care about the money. I just want to know why the prosecutors who hid evidence, sent me to prison for something I didn't do and nearly had me killed are not in jail themselves. There were no ethics charges against them, no criminal charges, no one was fired and now, according to the Supreme Court, no one can be sued."

Deliberate Indifference

The prosecutorial misconduct in Thompson's case was no anomaly. According to a report by the Innocence Project of New Orleans, District Attorney Harry F. Connick's office withheld evidence favorable to the defense in at least nine death row cases. Four death row convictions were overturned because of the misconduct.

In spite of this legacy, the Supreme Court ruled1 that the violation in the Thompson case was "a single incident," and that no pattern of misconduct could be established. The majority opinion acknowledges the four other overturned convictions but argues that they don't count because different types of evidence were withheld in those cases. In her dissent, Justice Ginsburg writes, "the conceded, long-concealed prosecutorial transgressions were neither isolated nor atypical." She cites ten items of evidence that were withheld from Thompson's defense, including police reports, audiotapes and blood evidence that would have seriously undermined Thompson's conviction.

Copyright 2015, Innocense Project

From: Innocence Project, "Holding Prosecutors Accountable," August 31, 2011, http://www.innocenceproject.org/news-events-exonerations/holding-prosecutors-accountable, accessed 07/11/2015. Reprinted in accordance with the "fair use" provision of Title 17 U.S.C.§ 107 for a non-profit educational purpose.

Reference

- Connick v. Thompson, 563 U.S. ____ (2011).

Additional Reading

- Brian Rogers, "Prosecutor in Graves case disbarred in rare move," Houston Chronicle, June 12, 2015.

- 48 Hours: "Grave Injustice," CBS News, March 19, 2012, http://www.cbsnews.com/news/students-help-free-wrongfully-convicted-man-19-03-2012/, accessed 07/04/2015.

- Crimesider Staff, "DA disbarred for sending Texas man to death row," CBS/AP, June 12, 2015, http://www.cbsnews.com/news/charles-sebasta-prosecutor-of-wrongfully-convicted-man-anthony-graves-loses-law-license/, accessed 07/04/2015.

- Tulanelink.com, "Prosecutorial Misconduct; Glenn Ford was freed after nearly 30 years in Louisiana's Angola Penitentiary."

- Tulanelink.com, "Charles Sebesta 'Disciplined' for Prosecutorial Misconduct; Anthony Graves spent 18 years in prison, including 12 years on death row, for murders he didn't commit."

- Tulanelink.com, "Deceptive Prosecutors Ruled Immune from Accountability

(Part 1) ; John Thompson spent 18 years in prison, including 14 years on death row, for a murder he didn't commit."

- Tulanelink.com,"Dishonest Prosecutor Receives Slap on Hand."

- Judge Kozinski speaks out on the origins and consequences of prosecutorial misconduct and the critical need for reform.

Censure Judge Berrigan?

Web site created November, 1998 This section last modified July, 2015

| Home Page | Site Map | About Bernofsky | Curriculum Vitae | Lawsuits | Case Calendar |

| Judicial Misconduct | Judicial Reform | Contact | Interviews | Disclaimer |

This Web site is not associated with Tulane University or its affiliates

© 1998-2015 Carl Bernofsky - All rights reserved